While Champagne is often incorrectly used to describe any sparkling wine, the first important fact about this region is that “while all Champagnes may be sparkling wines, not all sparkling wines are Champagne!”

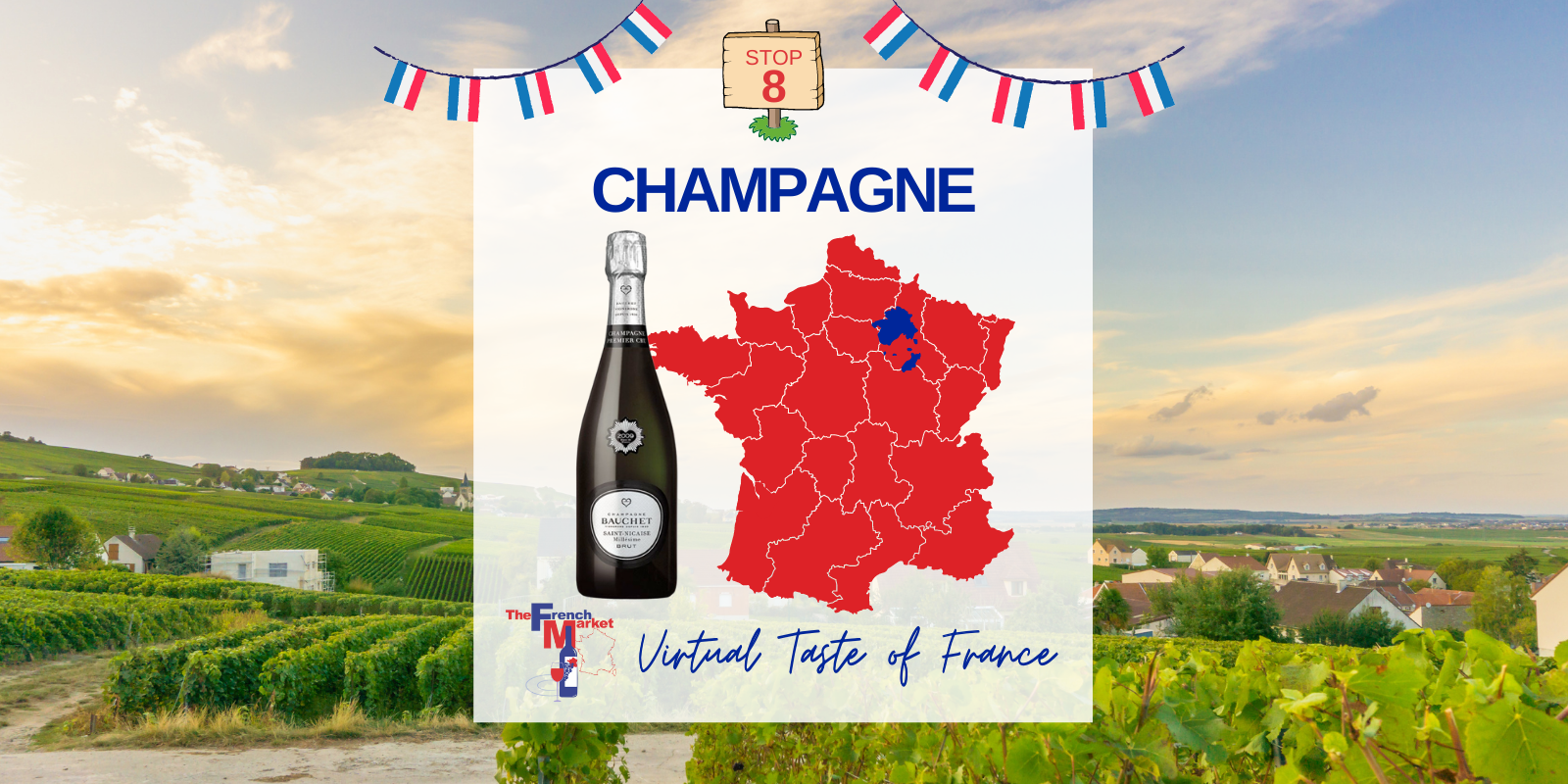

Located in the northeast of France, the Champagne wine region is the closest of all French winemaking regions to Paris (about 100km, or an hour’s drive east), and is the home of true Champagne, renowned around the world, and enjoyed most famously during celebrations and special occasions.

At the northern limit of the winemaking world, Champagne is the coolest of all the French winemaking regions, and unsurprisingly the climate dictates the type of grapes grown here and influences the style of wine produced.

Also important is the typically chalky soil which provides good drainage and also helps mitigate against cooler temperatures by absorbing the sun’s heat during the day and releasing it slowly at night.

As with elsewhere in France, winemaking in Champagne dates back to the Romans. While it wasn’t as prolific as other regions historically, still wines have long been produced here, though it wasn’t until the 17th century that the sparkling wine synonymous with the regions was developed, heavily influenced by the climate but also, in fact, by accident, when growers from the region who were trying, unsuccessfully, to emulate still wines from Burgundy. In the cool winter, the temperature drop stopped fermentation, but when spring came and temperatures rose again, fermentation started again in the bottled wine, releasing carbon dioxide and giving the wines its characteristic carbonation.

A surprising fact for many is that for a wine thought of as light and white, Champagne is actually predominantly made from red grapes. White wine can be made from red grapes provided they are pressed gently as most of the pigmentation in red wine comes from the skin. There are limits on how much juice can be squeezed out of a given weight of grapes, with the best juice coming from the first pressing.

The three main grapes used in the region are Chardonnay (which accounts for around 30% of the region’s plantings), Pinot Noir (40%) and Pinot Meunier (30%), and are among the very few varieties capable of performing in the colder, wet climate of northern France. The first two varieties need no introduction, and Pinot Meunier is a relative of Pinot Noir which matures earlier in the season and is in fact the one grape that will reliably ripen across the whole region. These three primary varieties account for almost 99% of all plantings of Champagne’s vineyards, but there are a further four grapes approved: Petit Meslier, Arbane, Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc. Each variety has its own benefits – Pinot Noir brings strength and body, Chardonnay brings finesse and floral notes, while the Pinot Meunier brings a certain fruitiness most obvious in younger wines.

This leads us to another key feature of Champagne production – blending. We’ve already seen that there are three principle grapes and most Champagne will feature some combination of these, but Champagnes are typically also blends of different crus (growths) and vintages (years). By combining wines with different colours, aromas and flavours the Champagne maker looks to create a wine that is greater than the sum of its parts. Blending also allows the winemaker to achieve a consistency of style across different vintages. The blending process can take several weeks, testing several combinations before finalising a blend, and it is usually the work of a skilled team rather than an individual. Most of the blending is done in “Champagne houses” who typically grow little or none of their own grapes, instead purchasing from smaller growers and blending and finishing the wines before releasing under their own label. Recent years have seen a rise in grower-producers producing more single-vintage, single-vineyard, single-variety Champagnes, but these are still a fraction of the overall market and typically much harder to find.

Some other unique types of Champagne to look out for:

- Single vintages are typically only produced in the years deemed best by producers, and tend to be much more expensive

- “Blanc de Blancs” are made only from white grapes (Chardonnay) and are typically very sharp when young but develop a prized honeyed richness with age.

- Blanc de noirs (“white from black”) are of the opposite – a white Champagne made from the red grapes Pinot Noir and/or Pinot Meunier. As we’ve already touched on, white wines can be made by gently pressing red grapes, but these still have a characteristic rose-gold colort. They are powerful when young, but still approachable because of their often fruit aromas and palatte.

- Rosé Champagne – as rosé wine has become more popular, so has rosé Champagne, which is one of the only regions where rosé is made by blending red and white wines.